LP1425 11x14”

Semmendinger Field View Camera

- Rehabilitation and Rear Platform Reproduction -

____________________________________________

LP1425 is a large wet-plate Semmendinger Excelsior Variation 1 view camera purchased on eBay on 11 Nov 2023. It was apparent from the eBay photos that it was a folding field camera, but that it was missing the rear platform that was probably hinged at one time to the main platform.

Photo 1: eBay photos of camera as received. The damage to the rear of the main platform is not visible in any, but the lack of a rear platform is evident.

Since I have made approximately a half dozen camera backs/ground glass frames utilizing the type of wood joint (bridle joint) that the rear platform would have, I decided to buy it, and reproduce its rear platform to the best of my ability.

Upon receipt, I found that the rear platform was, indeed, missing, but,

in a minor miracle, the two large bolts that are used to make the rear

and main platforms rigid were contained in the little compartment at the

lower part of the front standard.

I also found out why the rear platform is missing – in some kind

of dropping incident, the rear platform pulled out both hinges from the

main platform, as well as a significant amount of wood at the right

hinge, and a large part of the right side of the t-shaped channel used

for the brass combined fine-focus screw/focus lock device, which is also

missing. In addition, one of

the brass tracks on which the rear standard rides was quite bent, being

screwed to a part of the camera which is now missing.

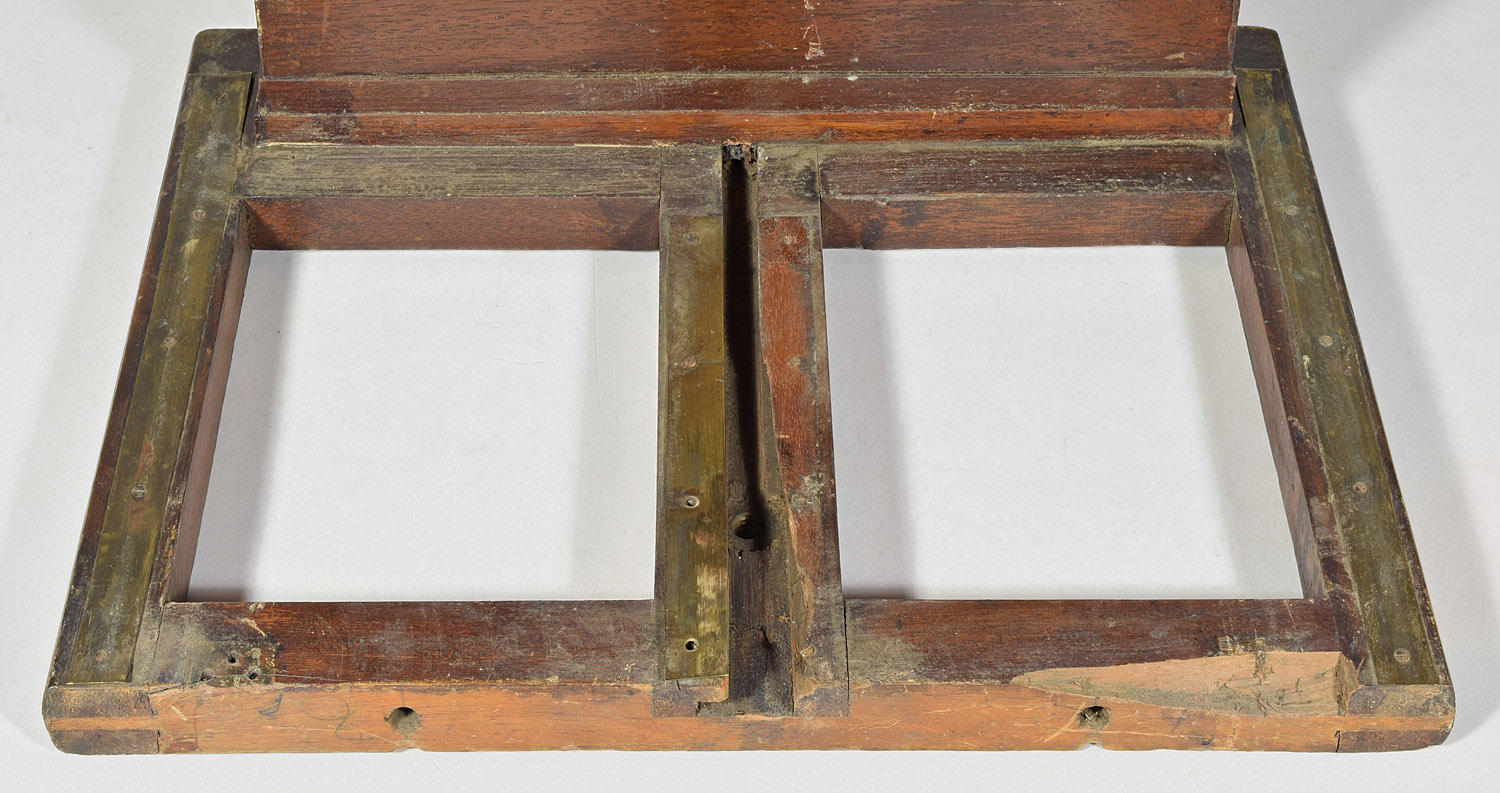

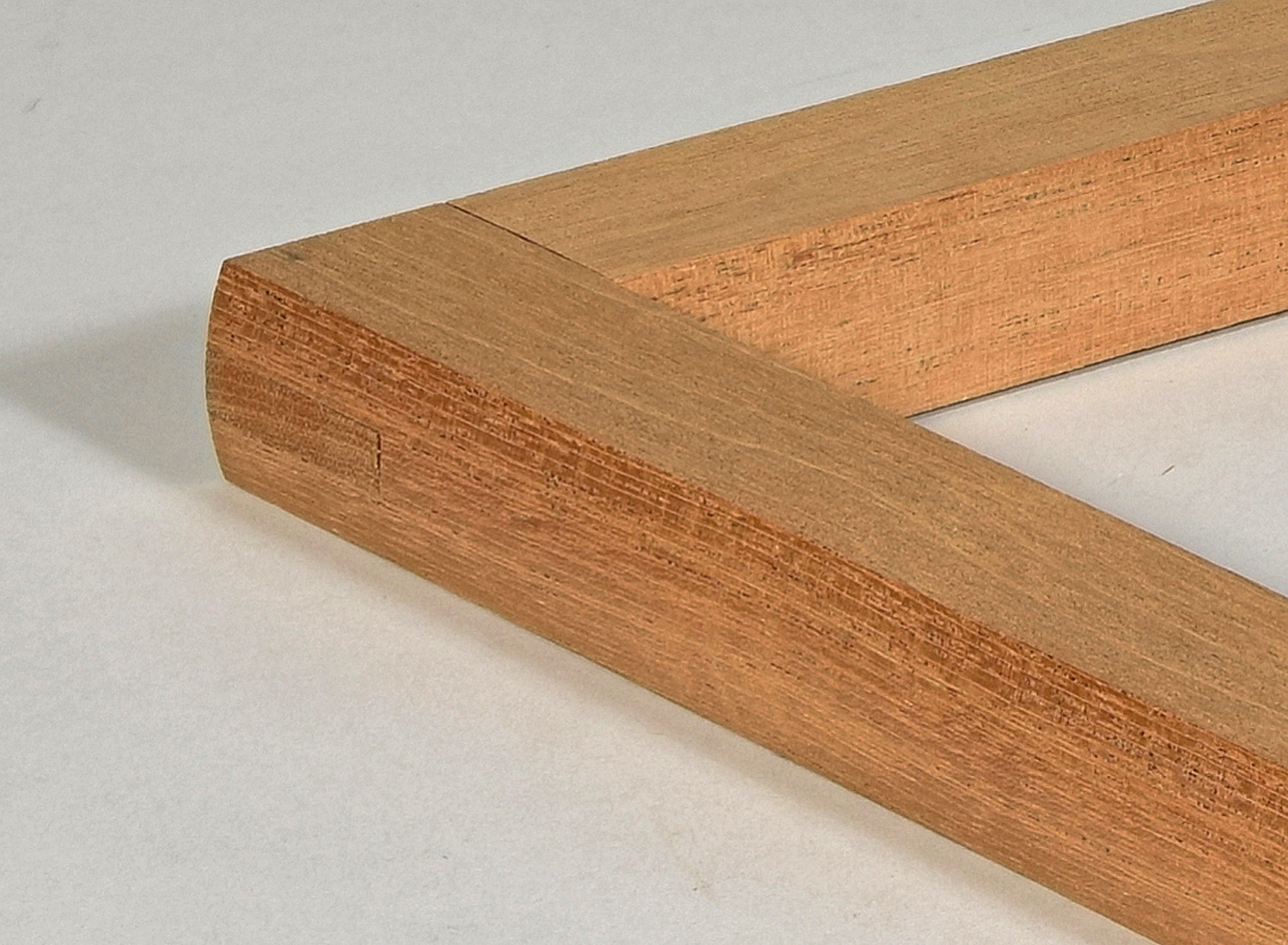

Photo 3:

Close-up of the right rear side of the main platform.

The missing wood extends almost half-way through the rear

cross-member.

The wood comprising the main platform is 15/16” thick and 1 3/16” wide. Paul Semmendinger, who keeps track of extant Semmendinger cameras (current count, 33) was able to take photos and take measurements of another 11x14” folding field camera, where we found out that the rear frame to be reproduced is 19” long by 15” wide. The sides and ends of the frame are 1 3/16” wide, and there is a 2” wide piece running down the center that has a t-shaped slot for the fine focus device.

1. Wood

Mahogany is a

collective term referring to about 30 different species of reddish

hardwood. The species used in the 1800’s for camera manufacture is

no longer readily available. The closest mahogany to antique

camera wood is called genuine mahogany in the hardwoods store I

frequent. I think this same wood was called Honduras mahogany at

one time. So this was the wood I chose with which to make the rear

platform.

The thickness of hardwood called 1” nominal thickness

is actually 13/16”. This is 1/8” too thin. I therefore had to buy

a 2” nominal thickness board (actually 1 3/4”) and have it planed down

to 1” thickness. I planned on having the frame sanded in a 3’ wide

sander that they have at the hardwood store, so I didn’t have it planned

to exactly 15/16”. I will also make the dimensions of the frame

1/4” larger than the original (1/8” per edge), so that it can be trimmed

to exact measurements after it is glued together.

The woodworking tools used will be a circular saw for

rough cutting, a table saw for fine cutting, a jig for holding wood

straight up while being cut in the table saw, a router for the t-slot,

and a set of 4 clamps having right angles to glue the frame precisely.

2. Center Rail with T-Slot

I thought that the center rail, with its T-shaped slot for the fine focus screw would be the trickiest to reproduce, so I started with this first. I had never done something like this, whereas the rest of the rear platform would be four pieces of wood connected with bridle joints, the same type of joint that I had used to make a number of missing ground glass frames/backs. It’s not exactly a “T”, but rather an upside-down “T”.

Photo 4:

Close-up of the end of the original center rail of the main

platform

It turns out that router bits that cut a T-shaped slot do exist, but not

in the size necessary to match the one in the main platform, which has a

vertical part 1/2” wide, and a horizontal part (the top of the T) 1”

wide and 1/4” high. Thinking

of them as separate was the key to doing it.

A 1/2” diameter straight router bit does the vertical of the “T”,

and there is a router bit that will do a 1” x 1/4” hole, once the 1/2”

vertical has already been cut.

The router has a 6” diameter round platen, the bit being held in the

middle, 3” from the edge. So

I could set up a fence using a straight board, which the router platen

could slide down. The center

rail is 2” wide, so the fence has to be 4” from one edge of the center

rail. Obviously, the slot

had to be cut before the center rail was cut to final size.

I used a large piece of maple plywood that I had used to make

shelves (to hold cameras, of course) for a flat substrate unlikely to

cause the router to wiggle or pause.

To this was clamped a full width (6”) piece of my 1’ thick

mahogany, and a 1x2” piece of pine that had a straight edge as the

fence. The fence was

positioned 4” from the trimmed, straight edge of the mahogany.

It was really easy to keep the two cuts centered with each other – don’t

move the fence. I realized

that I could merely make one cut after the other (adjusting for proper

depth when changing bits) and it was done.

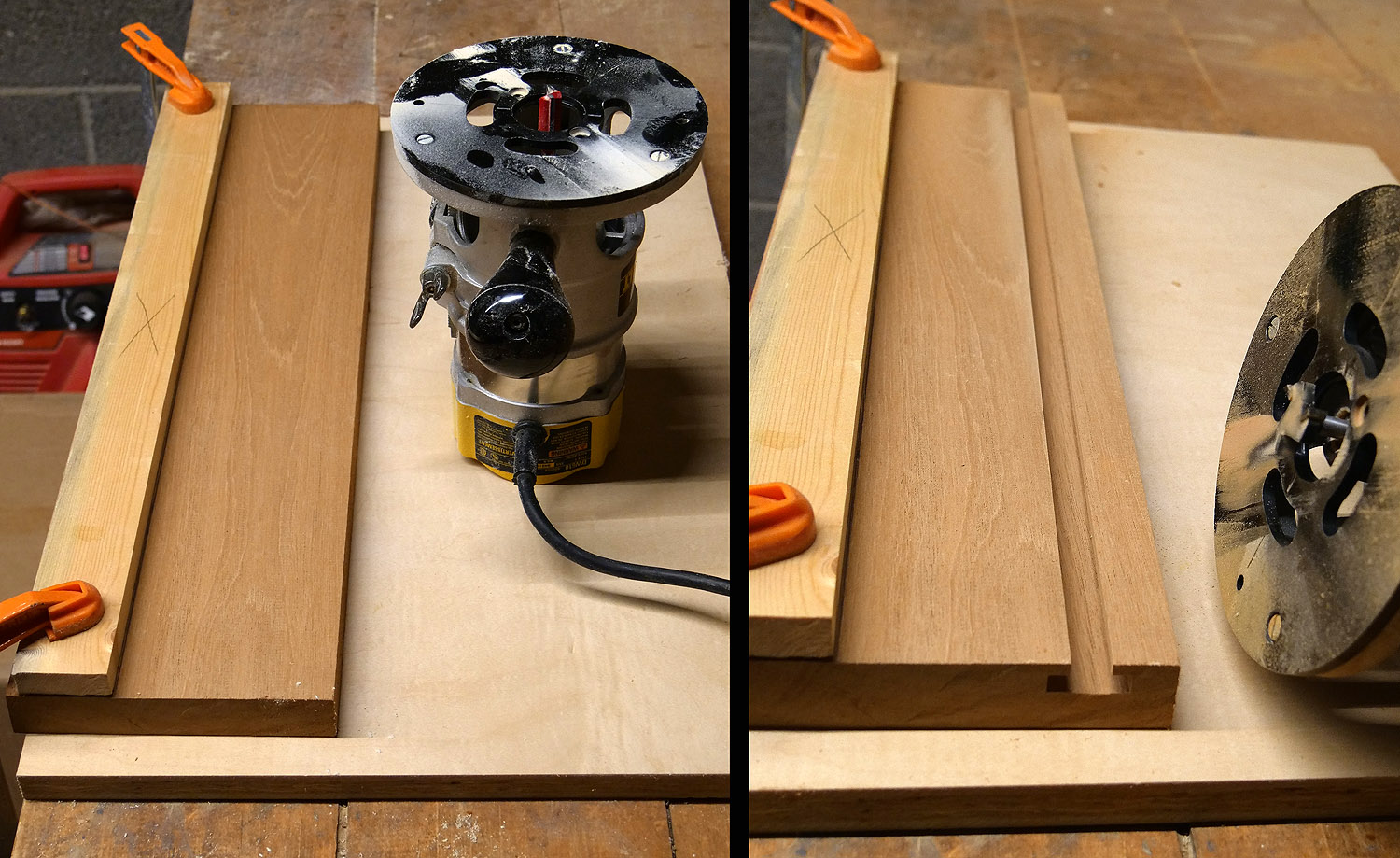

Photo 5:

The cutting of the “T”-slot for the new rear platform.

Left: before cuts.

Right: after both cuts.

All that was necessary to finish the center rail was to rip the piece to

2” wide.

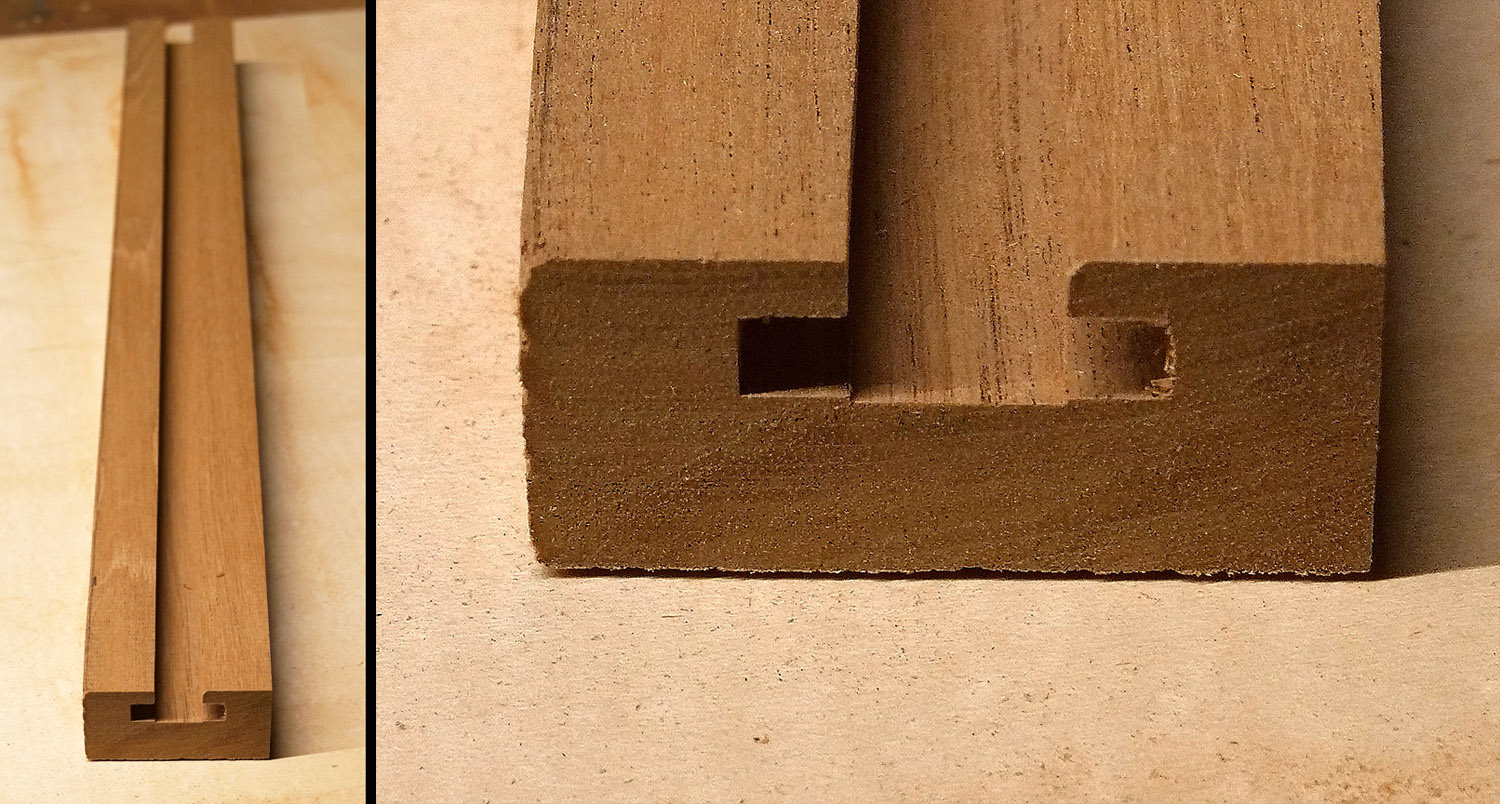

Photo 6:

The center rail to size.

Left: full shot.

Right: close-up of one end.

3. Side Rails

The side rails are to be 19 1/8” long, 1/8” longer than the final

length, leaving 1/8” to be allowed for some slight trim on all sides

that will even up some misfit of the joints.

The joints at the corners are bridle joints, which require a slot to be

made in the side rails and two rabbets on the end rails that will create

a block at each end to fit into the slots.

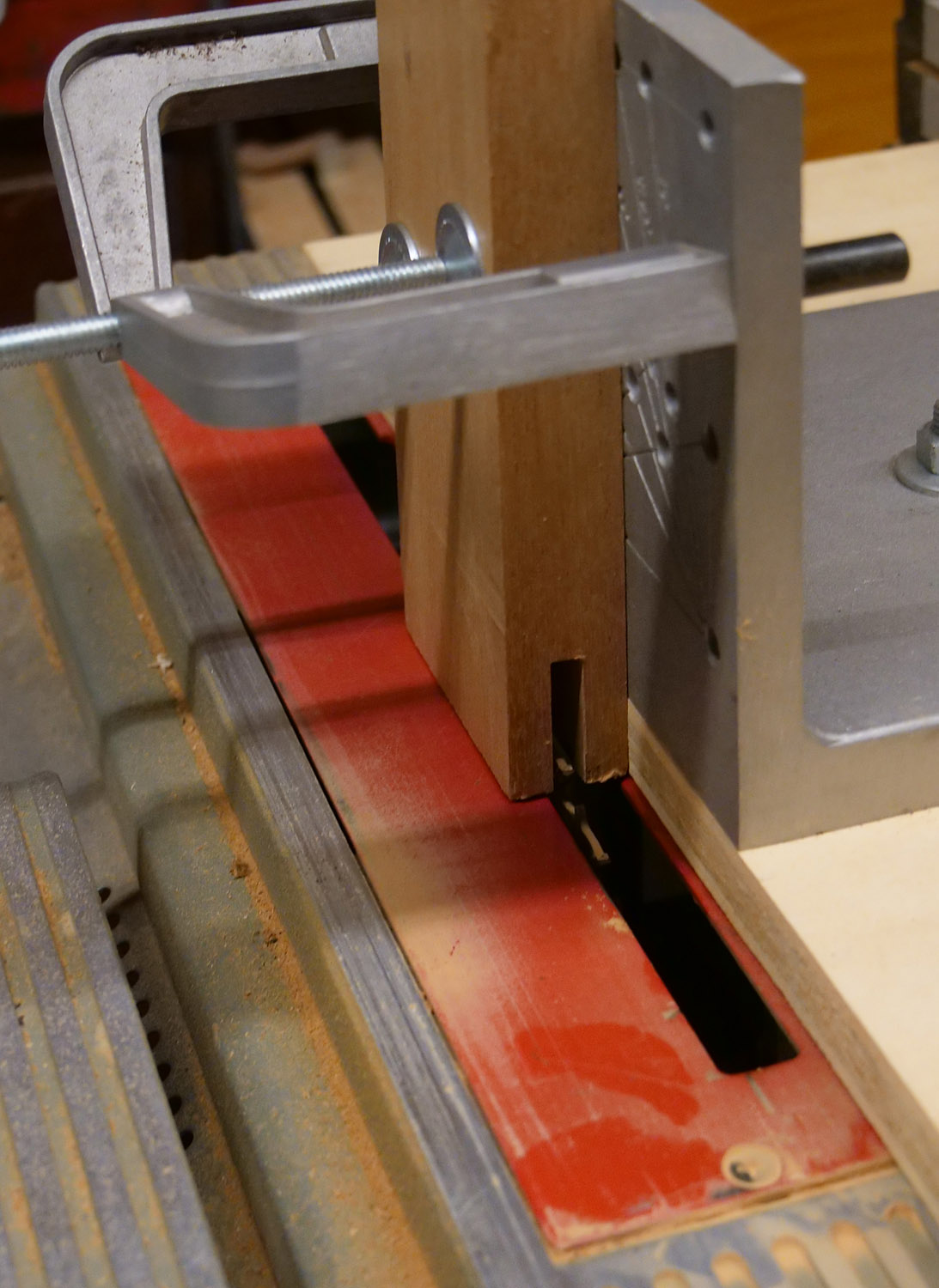

Photo 7: Cutting a slot in

the side rails. The rails

are still one piece for now.

This is the first cut, made with a normal saw blade.

The piece will be removed and turned around for the second cut in

order to make a perfectly centered slot.

A centered slot will allow all the rabbets to be cut to the same

depth. The depth is 1 1/4” (1/16” greater than the projected final

depth).

Photo 8: Cutting the first

rabbet on the end rails (which haven’t been ripped to width yet to make

the rabbets exactly the same for each rail.

Both rabbets on this end will be cut, then test fitted to the

already cut slots in the side rails, the cut a little deeper until the

end fits in the slot.

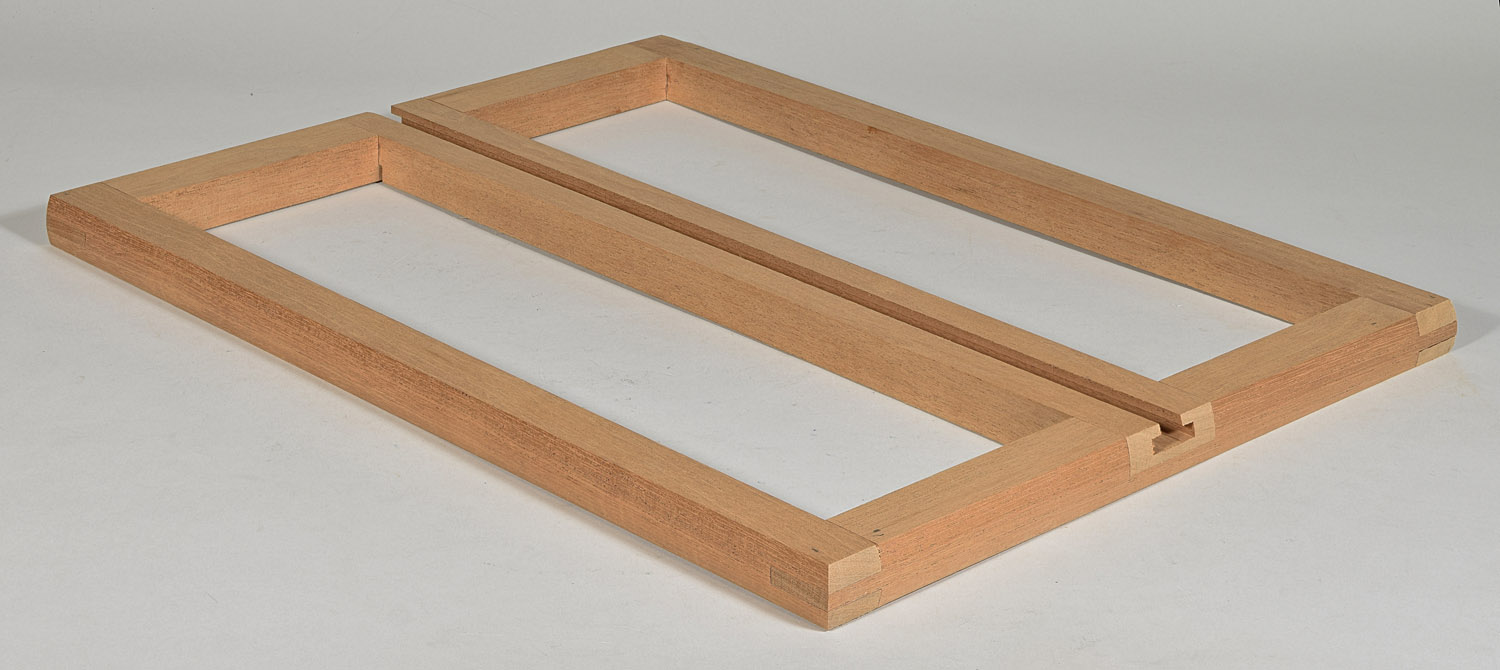

Photo 9 (left):

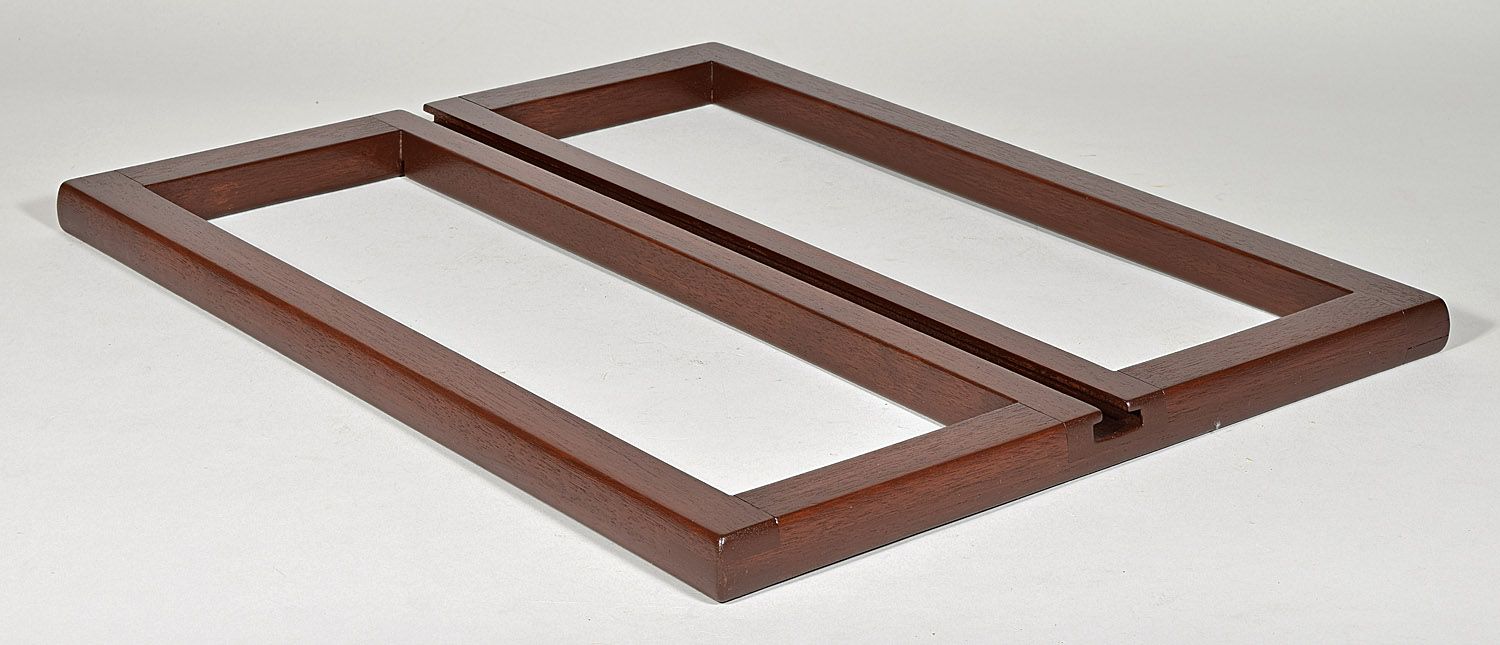

The finished two ends (left), two sides (middle), and center rail

(right).

Photo 10 (right):

A dry-fit of the parts.

4. Assembly

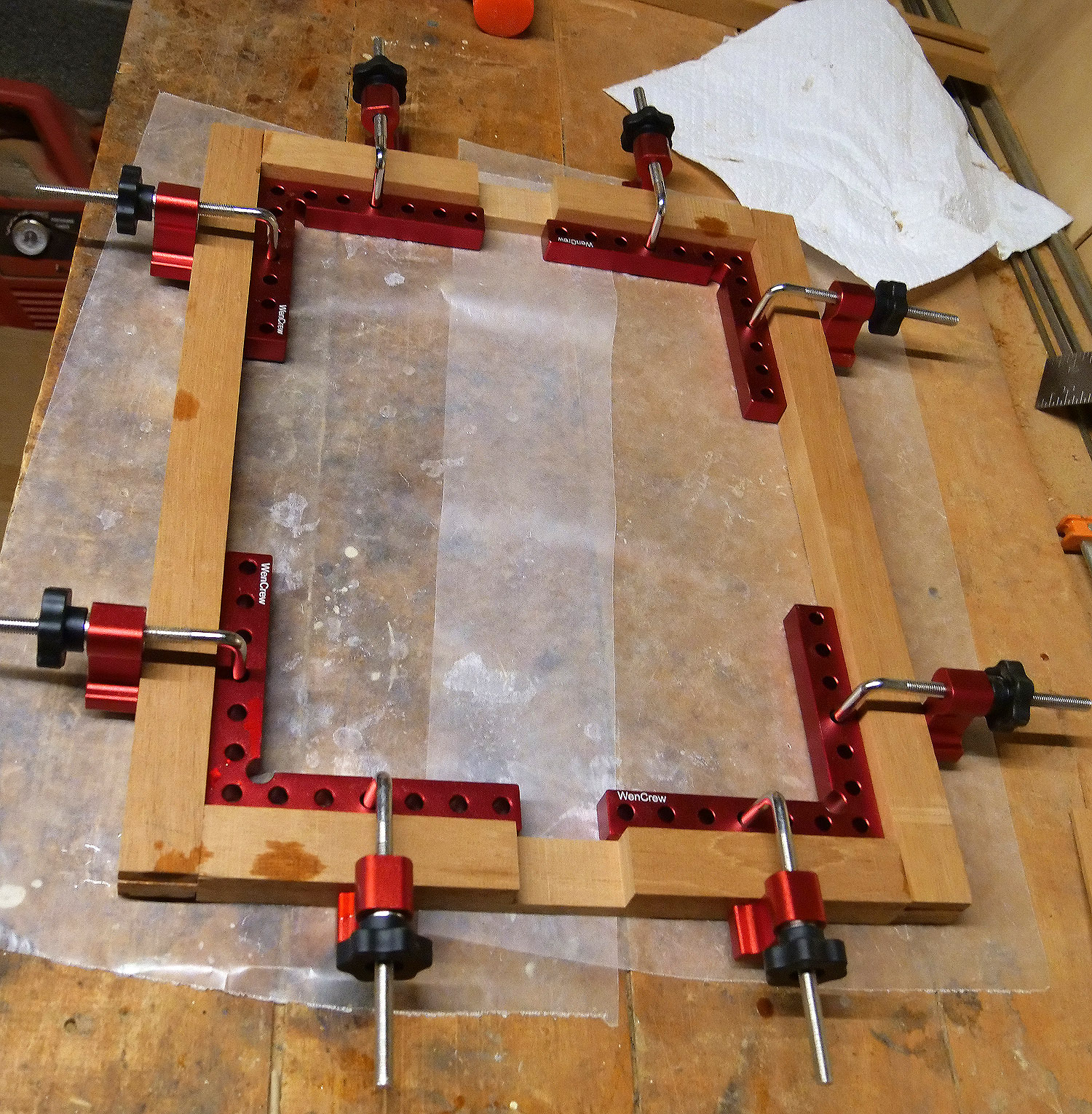

To glue the ends and sides together, a commercial corner-jig setup is

used, consisting of four square corners, each of which is clamped to an

end and a side.

Photo 11:

Gluing the ends and sides.

Then the center rail is glued.

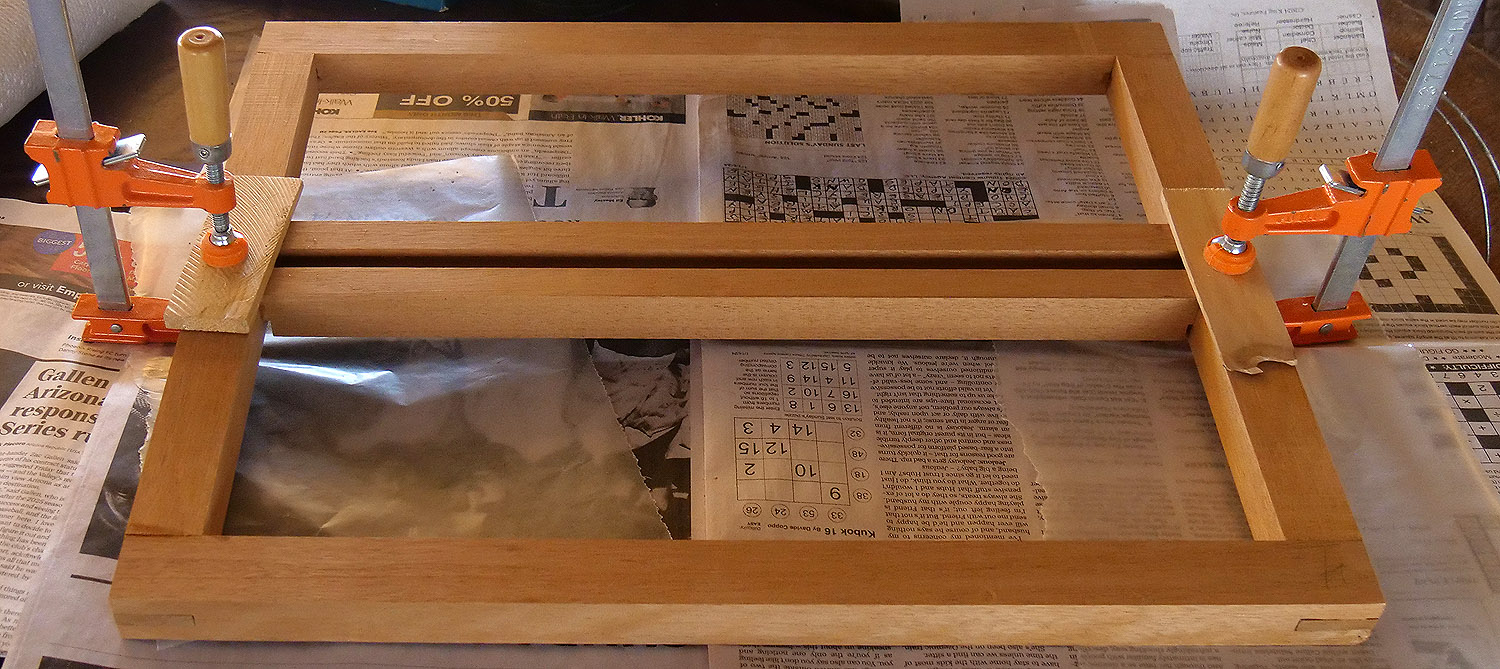

Photo 12:

Gluing the center rail.

Since the stock was 1” thick and the original camera rails are 15/16”

thick, the assembly was taken to a woodworker’s shop that had a large

sanding belt. The front was

minimally sanded (we don’t want to make the t-slot any shallower than it

already is), and the back sanded until the thickness was 15/16”.

The original sides are slightly rounded, which presents a problem.

The closest solution was to use a

1 1/2” Convex Edge Oval Router Bit

(the largest available, since they are usually used for stair treads).

To use a 1 1/2” tall bit on a 15/16” thick edge, the frame had to

be clamped on a pedestal (to make the middle of the over-large bit

coincide with the middle of the frame edge), then a large flat and

smooth piece of wood was clamped on top of the pedestal for the router

plate to slide on. Finally,

a wooden fence was clamped on of the smooth piece to keep the router

parallel to the edge. The

distance from the fence to the edge of the frame was determined by trial

and error – starting too close and gradually attempting to remove wood

at the top and bottom of the frame but not in the middle.

It turned out that I misread the amount of wood removed, and

ended up taking off about 1/16” on each side of the frame.

It is now slightly less wide than the original.

For about 1 second, I considered starting over and making a

second frame, but it was about two weeks work - so, no.

Photo 13:

After Sanding and Edge Rounding.

Photo 14:

Close-up of Edge Rounding.

The photos above show sharply cut edges, whereas the camera has

eased,

i.e., slightly rounded edges.

This was done during final hand sanding with 100, 150, 220 and

320 grit sandpaper.

5. Wood Finishing

It appeared that the camera color was very near a red mahogany gel stain

that I had, but the platform was much darker along the edges, and rather

light on vertical surfaces.

This was only noticed after some staining had already taken place, so is

only of use as a post-mortem.

To obtain an even stain, the wood must first be sealed with a thin coat

of spray shellac. This

prevents the stain from soaking in unevenly.

Mahogany is not as uneven as other woods, such as cherry and

pine, so it may not have been necessary, but with the amount of work

going into the platform, it couldn’t hurt.

Photo 15:

Red mahogany gel stain base coat.

Then, when it was a good match for the camera

body, but too light and red for the camera platform, a coat of American

Walnut was added. I should

have only put it on the top and sides, leaving the vertical surfaces

lighter, but too late now.

Photo 16:

American walnut over red mahogany gel stains.

This is much closer to the color of the top and sides of the original

platform, but the stain is too uniform to suit me.

The work involved in stripping it and re-staining, though,

convinces me to not mess with it any more.

From the distance in a usual museum display, the reproduced part

is convincing enough.

As usual, I stamped my initials and date – LP 2024 – into the bottom of

the reproduced part so that there is no doubt that this is a reproduced

part. I rubbed black paint

into it so that it is visible but subtle.

6. Making the Rear Platform

Functional

The original rear platform was ripped off the main platform leaving two

stripped screw holes from which the hinge was pulled out on the left

side, and leaving a missing piece of the main platform on the right

side. There is also a piece

of wood missing from the right side of the center t-slot, which would

prevent the rear standard from being locked when the camera is folded –

that is, if I can ever obtain a fine focus mechanism that fits.

Photo

17: Damage at the rear of

the main platform.

The screw holes on the left side were filled in using my personal

formula wood filler, consisting of mahogany saw dust mixed with enough

hide glue to make a paste.

The hide glue is soluble in hot water, so the fix is technically

reversible, although I certainly wouldn’t want to try to get them out of

those holes.

The missing piece on the right is not just a cosmetic problem.

The missing piece contained the right hand hinge for the rear

platform – a necessary part for the rear platform to be functional.

The missing chip extends into the platform about 3/8”, stopping

right where the middle slot and rabbet start in the bridal joint.

The right edge of the missing piece runs along the left edge of

the side rail. If I tried to

make a piece to fit only in the missing hole, there is no way that it

could have a strong enough bond to the remaining wood to support a

hinge. So I decided to cut a

dado 1/3” deep extending from the right rail for 2 1/4”.

That would allow me to install a rectangular patch that would be

able to be strongly glued, even using hide glue.

The dado will be made as I usually make them – a series of circular saw

kerfs that span the required distance.

I this case, I cannot use the table saw because the front

standard will not come off of the main platform.

The three large screws that usually secure the front standard

came out easily, but someone must have glued the standard bottom rather

well, because I could not crack it loose, even using a chisel and hammer

(carefully). Therefore this

dado would be cut using a 4” diameter battery powered circular saw.

To keep the saw within the 2 1/4” boundary and to keep the saw

from cutting too deep, a board was clamped over the area to be cut, and

the boundaries drawn on the board.

Notice that the dado has been purposely left short of the hole in

the end of the platform that accepts one of the 5/16” thumbscrews that

make the two platforms rigid.

I certainly didn’t want to try to duplicate the inlet brass piece

that is present on the far side of the hole.

Photo 18:

Set-up for dado for hinge patch.

The cuts did not turn out as slick as anticipated.

As the top board gradually got cut away, instability in the saw

caused some cuts to slightly lower than planned.

Photo 19:

Completed dado for hinge patch.

Not enough to prevent a good bond with the hinge

patch, however.

Photo 20:

Hinge patch before being glued into the patch dado.

The hinge patch was glued with hide glue, as

usual. The small crack

caused by saw blade drop was stuffed with my mahogany sawdust/hide glue

wood dough.

5. Final Touches

The rear platform was originally attached to the main platform by six

screw hinges (three on each side).

I would have used replacement hinges of the same size if I could

have only found some. I

therefore turned to my collection of antique camera pieces and parts,

and found two matching 6 screw hinges having a nice patina similar to

the original brass parts on the camera, that are slightly larger and

probably stronger that the originals.

To find the exact spots to drill holes in the rear platform to match the

locations of the originals in the main platform, I used a very sharp

drill, pushed from the inside of the original holes to mark the center

of holes to drill in the rear platform.

Using a drill 1/64” larger than the 5/16” thumbscrews that will

go through them, I drilled holes, attempting to keep the drill at right

angles to the rear platform.

Below is a photo of the rear platform with hinges and thumbscrews

providing a rigid connection to the main platform.

Photo 21:

Hinges and thumbscrews finished.

Another small detail remaining is the missing wood in the center rail of

the main platform.

Photo 22:

Missing wood in center rail of main platform.

I decided to patch this, since the rear standard could not be fixed for

transport without this vital missing piece.

Also, the brass strip that is to be re-installed over the missing

piece cannot be firmly attached without it.

The metal strip had been bent back on itself due to the

instability caused by the missing wood.

The other brass strip was held only by one screw and a nail, the

bottom two screws being missing.

A paper pattern of the missing wood was made by pressing Xerox paper

against the break to create a crease, then cutting along the crease.

The pattern was then transferred to a practice center rail in

which I had previously routered the t-slot.

Photo 23:

Transferring the pattern of break to a practice center rail.

A 1/4” chisel was used to create a scored line

matching the line of the break, but slightly larger.

Further chiseling caused the piece to break approximately like

the original camera piece broke.

The piece was then laboriously carved with wood carving tools

into a condition where it fit more or less into the missing area.

The piece was then glued and clamped into position.

Any remaining cracks were filled with the type of wood dough

discussed above.

Photo 24:

The patch installed.

The patch was then painted, using a 1/4” brush, with stains to match the

surrounding wood.

The screws originally used to fasten the brass strips along the center

rail (and probably all the screws in brass strips wherever they are)

were No. 3 and 1/4” long, which only have a few threads.

The screw holes were no doubt stripped when the accident

happened. The screws were

located above full thickness wood, so there is no reason to keep using

1/4” screws. So the screws

of both strips on the center rail were replaced with 1/2” No. 3 screws

after pre-drilling the holes for the greater depth.

The exceptions were 1) one location in the left hand strip, which

had been nailed after the accident, and the nail could not be removed

without damaging the strip, and 2) the location over the largest part of

the new patch in the right side of the center rail.

The crack in the rail had run directly through this screw

location, so any attempt to screw into that location would be liable to

start a crack between the patch and the rail.

In this case, a No. 3 screw 3/4” length was used.

The pre-drilling included a normal diameter hole 3/4” deep but

also a greater diameter hole 1/4” deep, to prevent the screw from

pushing the patch away from the rail. The

pre-drilling succeeded, as can be shown in the photo below.

Photo 25:

Original brass strips re-installed over the patch.

6. Refinish of the Rear

Platform

The original main platform is much darker than the upper parts of the

camera. It may not even be

the same type of wood, as, although the grain in the fracture looked

like mahogany, the color of the platform is not as reddish as the more

obviously mahogany parts.

In trying to make the reproduction mahogany rear platform as dark as the

main platform, I used gel stain, which can be put on thicker than

old-style thin pigmented stains.

But by the time the part looked dark enough, the finish was thick

enough to look obscure the grain of the wood, and it looked more like

paint than stain. I

therefore took off the rear platform and removed the vast majority of

the it’s finish using a finish

restorer, a solvent capable of dissolving all kinds of finish,

gradually thinning the color.

I left some of the color on in areas, making it uneven, kind of

like the original main platform, which has been left uneven by rough

handling and wear. I sanded

the bottom and inside end of the platform, areas that hadn’t been

stained or finished on the original platform (I had failed to take these

differences in account when finishing it the first time.

The new darkening agent was an aniline dye, which dissolves in alcohol

to make a concentrated stain, and comes in as wide a variety of colors

as any other type of stain. Given the non-red color of the main

platform, dark walnut dye was used.

Dye has the advantage of not being a pigment, and can be made

darker without obscuring the wood grain, as happened during the first

wood finish.

The first application of dye and alcohol was not quite dark enough.

Putting another application on seemed to move the first dye

around somewhat, so it was decided to add dye to a solution of shellac

(conveniently also dissolved in alcohol).

I used a garnetlac preparation that I previously have used on

lots of lens board reproductions.

Garnetlac is the darkest of shellac types and is probably similar

to the shellac actually used in the 1800’s.

Using this garnetlac-dye for the second application resulted in a

color and darkness very near that of the original platform.

A final thin application of walnut gel stain to the sides of the

reproduction platform brought it as near to matching the main platform

as feasible.

Photo 26:

New rear platform (right) installed with period hinges to the

original main platform (left).

One thing that was evident when comparing the reproduction to the

original platform is that the underside should not have any stain or

finish at all – the original is just aged wood.

Therefore, in addition to removing my aborted first try at wood

finish, the underside was sanded to remove most of the stain, although

there are grain streaks that would require so much sanding as to change

the dimensions of the wood.

So the streaks were left. A

single application of walnut dye and alcohol was made to darken the wood

without the use of shellac or varnish.

Photo 27:

Bottom surface of replacement platform, with stamp indicating

year it was made.

Over time it might age to better match the original.

The bottom is stamped with my initials and the year, a procedure

that I have followed for all of my reproductions of camera parts, even

though it is not likely that anyone would mistake them for original

parts.

7. Little Metal Strips

The original main platform has thin metal strips on which the rear

standard rolls. A

measurement showed that the metal (brass) had a thickness of 30 gauge

(0.01 inch. Unfortunately,

the thinnest gauge brass that I could obtain was 26 gauge (0.015 inch).

I think the thicker metal is a plus, in that it has more metal to

which the wood screws can hold, making it less likely that the strips

will pull out over the screw heads, as happened to the main platform at

some point.

It is not obvious upon first look, but the original strips have two

widths – one width for strips on the center rail and a width for strips

on the side rails that is about 1/16” less.

Fortunately, I took the main platform with me to the metal

supplier, where we could measure the widths and adjust the cutting

machine accordingly. Oddly,

the width set on the giant machine wasn’t what the width of the strip

coming out would be. We had

to cut by trial and error to get the widths desired.

The strips were left with slight burrs along each cut, a problem easily

removed using a steel file.

Each strip had to be fastened to the wooden rails by flat head, slotted,

brass wood screws. The

screws on the original part were separated by a little over 2 inches.

For our 19” long platform, a separation of 2 3/16” was used,

measured on the first, which was then used as a template to mark the

positions to be drilled for the others.

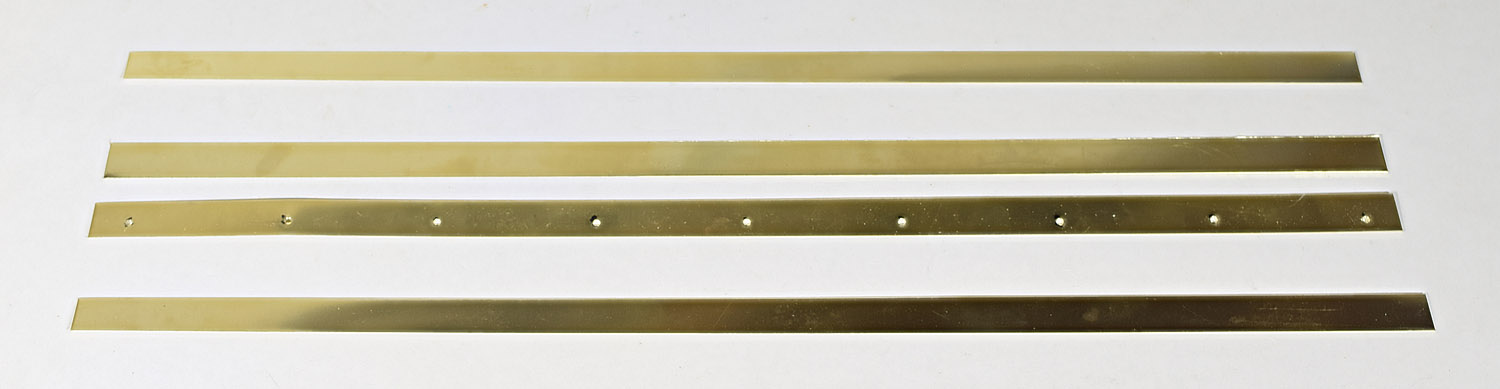

Photo 28:

The four brass strips for the rails.

One has had holes drilled.

The screws used for the original platform were No. 2 of varying lengths.

I used 3/8” long No. 2 for the new platform.

To simulate tarnish from age, the screws were first de-oiled by

soaking in denatured ethanol, then tarnished using a few drops of

Birchwood-Casey Brass Black.

The dilution of the brass black makes the reaction slow enough that one

can remove the screws at the desired darkness of tarnish.

The screw holes must be counter-sunk in order that the screws not stick

up and impede the movement of the rear standard.

After counter-sinking, the strips

were each tarnished using the same solution as for the screws, except

that the liquid had to be brushed on.

The result was not exactly uniform, but then the tarnish on the

original strips is not uniform either.

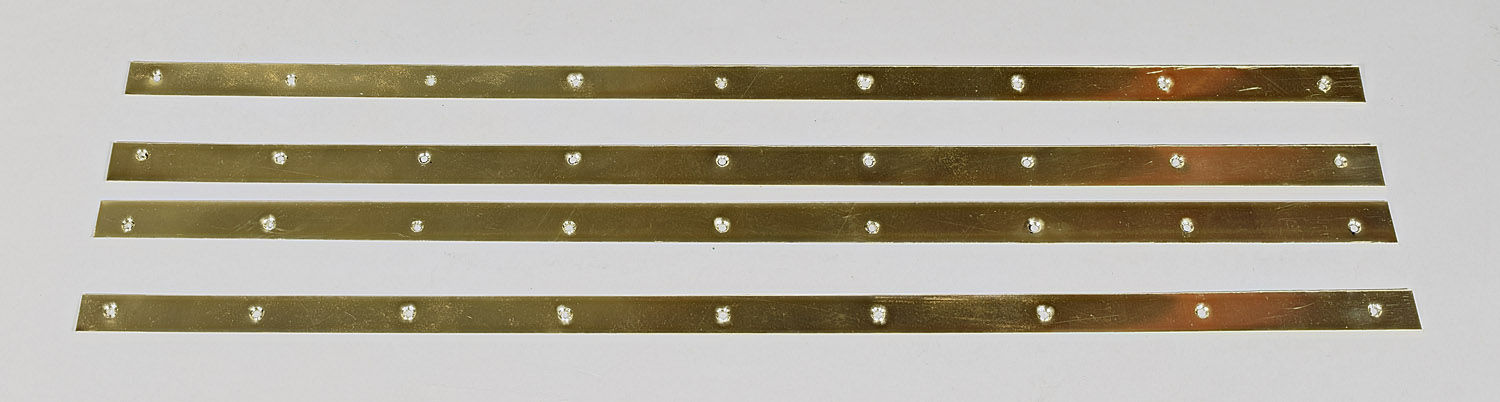

Photo 29:

The four brass strips, drilled, counter-sunk and tarnished.

The counter-sink bit did not cut cleanly.

When the brass got thin enough, it deformed into the shape of the

bit rather than being cut.

That the shape extended below the strip pointed out to me that

counter-sinking the brass alone would not be enough to provide room for

the heads of the wood screws.

So after marking and pre-drilling the screw holes, the wood was

also counter-sunk.

Photo 30:

The screw holes have been pre-drilled and counter-sunk.

The brass strips were then installed using the 3/8” long screws, without

the stripping of threads which may have happened without

pre-drilling and counter-sinking.

Photo 31:

Brass strips installed.

In tightening the screws, I even continued a practice seen in high-end

camera models: aligning the screw slots parallel to one another.

I had read that this was done by trial and error, eventually

finding screws that, by chance, tightened up to be parallel.

In this case, the screws felt like they could have been tight

enough over an angle greater than 180⁰.

That is, I never had to exchange screws to get them aligned.

Before reassembling the camera, it required cleaning, having probably

been stored in a basement, attic or garage for decades.

It was the dirtiest camera I have ever seen. It was cleaned with

damp paper towels, requiring as many as 10 such towels to clean a small

(10 sq. in.) area.

Below is a rear view of the finished camera, the rear standard supported

on its new rear platform.

Photo 32:

Reassembled Camera, showing the new platform in use.

8. Lens Board and Lens

The lens board that came with the camera is the original Semmendinger

lens board, which has two stamps:

Photo 33:

Stamps on upper lens board: “Excelsior” (left) and “A.

Semmendinger, Manuf’r / Fort Lee, N.J.” (right).

After the accident, however, the original lens undoubtedly required a

rear platform to be used.

The owner at that time bought a large wide angle lens, which could focus

with the rear standard on the main platform or just behind it.

But the original hole in the board (about 4” diameter) was larger

than the flange for the new lens. The owner installed a large and thick

board on top of the original lens board, and then installed the new lens

on it.

Since the lens board was original but the additional wood was ugly, I

decided to take off the additional wood, taking the board back to what

it was before the accident, despite the large number of scars from the

addition wood and many other holes.

It would have been nice to have an 11x14” lens (14-20” focal length)

whose flange was large enough to use the 4” hole, but even my 12x15” and

two 14x17” lenses are that large.

I had to use a 16x20” Somerville rapid rectilinear, which

installed without the problem of re-cutting the hole.

The lens may not focus, even with the bellows at full extension,

but it at least gets rid of the extra wood (and metal stars).

Photo 34:

Replacement 16x20” J.C. Somerville lens.

The relatively large holes left by the extra wood were filled with my

usual mahogany sawdust and hide glue wood filler.

The screw on top of the front standard that slowly moves the lens board

up or down was missing when purchased.

The replacement is a 1/4” x 20 threads per inch x 3” long solid

brass thumbscrew purchased on eBay.

The same solution of diluted brass black used for other brass

parts was used to tarnish/age it.

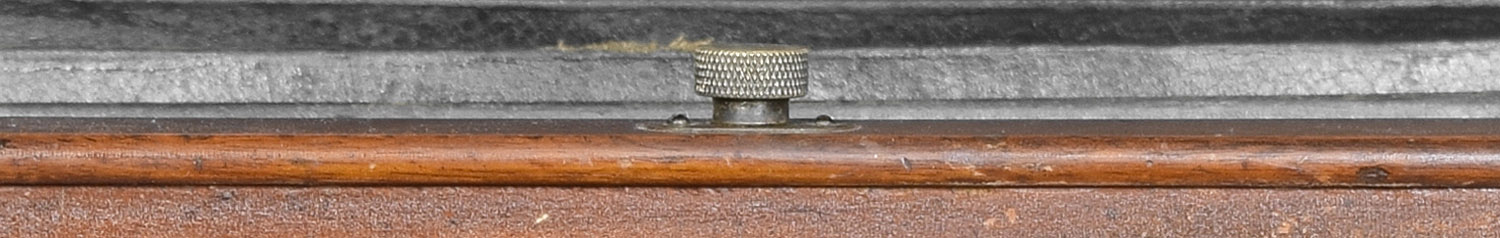

Photo 35:

Replacement Lens Board Rise Thumbscrew, Top of Front Standard.

Photo 36:

Completed and Reassembled Camera from the front.

Back to Semmendinger Variation 1