Scovill Mfg. Co.

American Optical Company

History of View Cameras and Relationship of Products

Scovill Mfg. Co. (Waterbury, CT)

American Optical Co., New York, NY (1858- )

American Optical Co., New Haven, CT

American Optical Div. Scovill Mfg. Co. (1867-1871)

American Optical Co., Scovill Mfg. Co., props. (1871-1889)

American Optical Co., Scovill & Adams Co., props. (1889-1902)

Scovill Mfg. Co.:

Scovill Mfg. Co., in the dry plate era (~1870-~1910), was a major supplier of cameras, lenses and other photographic materials, purchasing or merging with the companies: Samuel Peck & Co. (1860), American Optical Co. (1867), E. & H.T. Anthony & Co. (1899), and later, in the film era: IG Chemie (GAF).

Scovill Mfg. Co. was founded in 1802, producing non-ferrous, mainly brass and copper, items for the rapidly expanding economy of the industrial revolution. Scovill's factory was located on the Nagatuck River in Waterbury, CT. Their principal products were buttons, wrought brass butts and hinges, furniture casters, kerosene oil burners and lamps, thimbles, and many other products made of copper plated with silver or German silver such as coach lamps and and reflectors.

Upon the introduction of photography to the United States in the 1840's, Scovill was immediately capable of the manufacture of the silver-plated copper sheets required for the Daguerreotype photographic process. They rapidly became the main supplier of such plates as the number of photographers exploded.

Scovill gained the ability to manufacture the wooden parts of cameras by their purchase of Samuel Peck & Co. in 1860 (see below).

Samuel Peck & Co.:

Samuel Peck patented a device for holding Daguerreotype plates for polishing in 1850. In 1855, Samuel Peck & Co. was founded, and he entered into an agreement with Scovill Mfg. Co. The Peck factory was 12 miles downstream on the Nagatuck River to its confluence with the Housatonic River, and thence another 11 miles to Long Island Sound in New Haven, CT. It produced camera apparatus or boxes (using Scovill's brass hardware, of course), union cases (the cases for finished Daguerreotypes, and other photographic materials. By 1860, Peck had withdrawn from the business, and Scovill Mfg. Co. purchased Samuel Peck & Co. in that year. The factory continued to produce cameras and photographic materials. An 1876 Peck product catalog exists, so apparently until at least 1876, the factory continued to manufacture camera boxes under the Peck name. By 1885, however, products from this factory were marked or stamped Scovill Mfg. Co., New York, Scovill Mfg. Co., N.Y. or are unmarked as to maker.

John Stock & Co., the John Stock Camera Mfg. Co., and the C.C. Harrison Co.:

John Stock & Co. was founded in the late 1850's, manufacturing camera boxes in his New York City factory based on Stocks patents 1859, 1863, 1865 and 1872. Stock was considered to be building the best camera boxes in the United States. He also supplied all other supplies and apparatus for wet-plate photography, except lenses. To supply this missing piece of the photography supply business, he entered into a partnership in 1865 with the C.C. Harrison Co. (owner Nelson Wright), also of New York City, which held important lens patents. But late in 1865 or early in 1866, he sold out to newly incorporated American Optical Co., who had enough capital to buy both the C.C. Harrison factory and to license the John Stock patents. According to an article in Collector's Weekly (https://www.collectorsweekly.com/stories/69970-american-stereo-wetplate-camera-by-john), John Stock continued to make his cameras in the American Optical, i.e., his former, factory. Apparently, the John Stock factory became the American Optical Co. factory that would produce all the fine finished cameras sold by Scovill.

American Optical Co.:

American Optical Co. was founded in 1856 in New Haven, CT (the same town as the Peck factory) to manufacture camera boxes, stereoscopes, and photographic accessories. It was incorporated in late 1865-1866 as above, also doing business as the American Optical Co. They apparently acquired the John Stock factory at 207 and 209 Centre Street, New York, which continued to make the camera boxes (metal parts of which bear the inscription: "John Stock's Patent Aug. 1, 1863), and other wooden items and parts under the American Optical Co. name. The Harrison factory would have continued to concentrate on the lenses.

In 1867, Scovill Mfg. Co. purchased the American Optical Co. corporation, which became a division of Scovill. Until 1889, cameras manufactured at the American Optical factories were marked as such: American Optical Co., Scovill Mfg. Co., proprietors. After 1889, when Scovill Mfg. Co. was re-organized as The Scovill & Adams Co., American Optical cameras were marked (and no surprise here): American Optical Co., The Scovill & Adams Co., proprietors. American Optical cameras have either a German Silver-plated brass label, or their identity stamped into the wood. The labels during the Scovill & Adams years were cast celluloid rather than metal; they have an annoying habit of having the inscription easily worn off.

Scovill's Factories

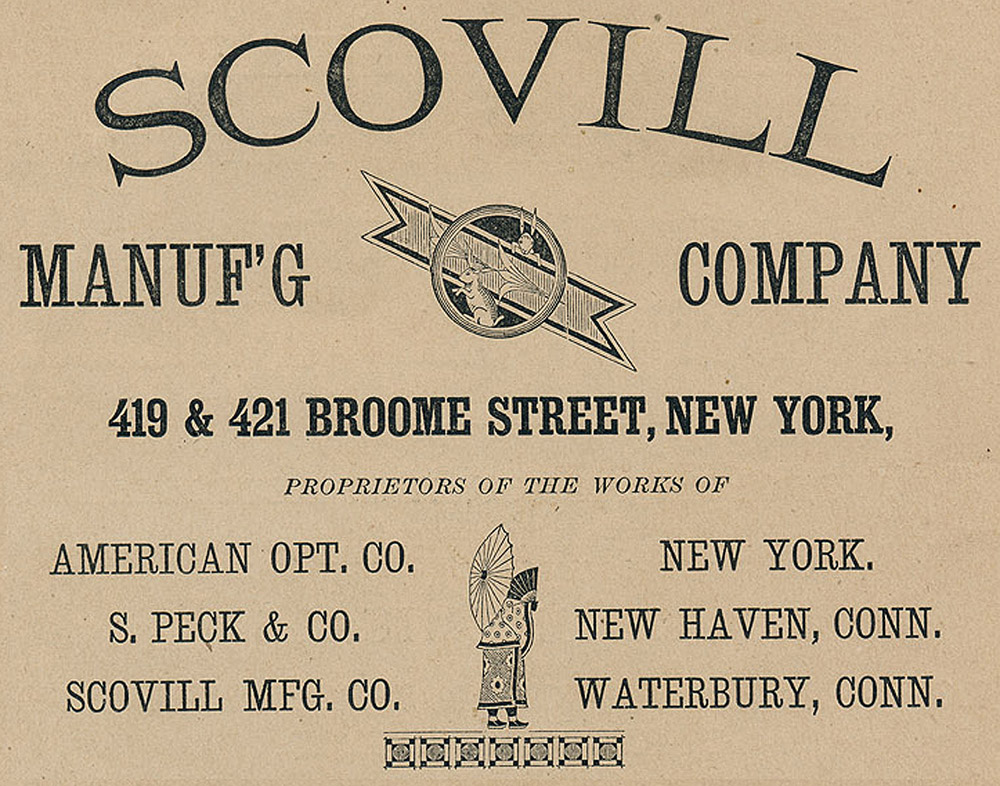

The

advertisement below, from the July 1880 issue of

The Photographic Times, Vol.

10, No. 116, back cover, .summarizes the

above information on factory locations. Scovill operated out of

four locations:

1) The offices were at 419 & 421 Broome Street, New York City, New

York. This location did not manufacture, being just offices.

2) The American Optical factory, the former John Stock Co., was in New

York City, NY, purchased with the company in 1867. This company

made camera boxes.

3) The S. Peck & Co. factory was in New Haven, CT, purchased sometime in

the late 1850's. This company also made camera boxes.

4) The Scovill Mfg. Co. factory was in Waterbury, CT. As a former

button factory, it probably manufactured the brass hardware and possibly

the brass barrels of lenses, such as

The Waterbury Lens.

There is no mention of the Harrison Co. factory that

should have continued to make lenses. It is possible that it was

close enough to the American Optical factory that Scovill thought of the

conglomerate of the former Stock factory and the former Harrison factory

as one factory - The American Optical factory.

Next, we shall see what having different factories means to the appearance of Scovill products.

American Optical Co. - Scovill Mfg. Co. Dichotomy of Quality:

As of the purchase of American Optical, Scovill Mfg. Co. had perhaps the premier lens manufacturing company in the United States and two camera box factories - the American Optical/John Stock factory in New York City, NY, and the Scovill/Samuel Peck factory in New Haven, CT. The two factories were already built, functioning and profitable, supply chains were in place, and the skilled cabinet makers in both locations must have preferred to continue working near their houses/apartments rather than relocating. Therefore, for many reasons, Scovill kept both factories in production.

Upon its acquisition, the American Optical-Stock factory had a line of cameras that included two general designs (straight bellows and tapered bellows) and three tiers of construction/finish. In 1871, for their most popular camera, a tapered-bellows view camera, there were three tiers: a best quality View Camera Boxes No. 1, a lowest quality View Camera Boxes No. 2, and a middle featured, plain View Camera Boxes. It is unknown whether the Samuel Peck Co. had a similar tiered system of camera quality.

What is observed on old cameras is that cameras having high quality are often marked American Optical, and cameras of low quality are usually marked Scovill. What appears to have happened between the acquisition and about 1885 is a company-wide tier system: the American Optical Co. (New York City factory) seems to have made the higher quality cameras and the Scovill Mfg. Co. (New Haven factory) seems to have made the lower quality cameras. This is usually readily apparent whenever a camera marked American Optical Co. is compared side-by-side with a camera marked Scovill Mfg. Co.

The specialization of finish quality even extends to cameras whose design is virtually the same. That is, for some models, American Optical has made a well-finished version at the same time that Scovill made a less well finished version. Two examples are The Waterbury View Camera and The 76 Camera.

The Waterbury Camera

In catalogs, The Waterbury View is always

implied to be a Scovill product, and, as to be expected, the examples of

cameras exactly like the catalog engravings are, indeed, marked as

Scovill. There appears to have been no camera of this type ever

advertised as an Optical Optical product. However, there are many

cameras extant that are almost identical in design and function as The

Waterbury View, only made from fancier wood, having fancier wood and

hardware finish, and marked as American Optical. See example,

below. That they were made in different factories seems to be

apparent from the differences between them: the physical size of

the American Optical version is significantly larger for a given plate

size. Also, some of the American Optical Waterbury-Type cameras

(here called

Waterbury-Type

Camera Variation 1) have a different system of hinging the

ground glass. Others (Waterbury-Type

Camera Variation 2) have the exact same hinging system.

If they were made in the same factory, it would not make sense to have

two different sizes of all the jigs and forms used to standardize the

manufacture, and they should therefore be the same size. Rather,

jigs and forms appear to have been made twice, once each factory, with

little regard to the detail of size, and thus came out different.

This conclusion is strengthened by our second example,

The 76 Camera.

Comparison of a 5x8"

American Optical Co. Waterbury-type Camera Variation 2

(left)to a 5x8"

Scovill Mg. Co. Waterbury Variation 1 (right). Note

that the design is essentially identical, though the sizes and details

are not.

The American Optical is constructed of

mahogany, French-polished piece by piece, and draw-filed brass, whereas

the Scovill version is constructed of varnished sycamore and unfiled

brass. The Scovill camera was varnished after the camera was put

together, saving much time.

The 76 Camera

A second example of the American Optical-Scovill

production dichotomy is The 76 Camera. In this case, the catalogs

always refer to The 76 Camera (in any of its four name

variations) as an American Optical product. As in the

Waterbury View case, the version made by the other factory - in

this case, a Scovill 76 Camera is never advertised. And,

as in the Waterbury View case, at least one example of a

76

Camera with Scovill markings exists (see examples below.).

And, as in the Waterbury View case, the physical sizes of the

two cameras are significantly different for the same plate size.

However, in this 76 Camera case, it is the Scovill camera

rather than the American Optical that is larger, whereas, in the

Waterbury View case, it is the American Optical that is larger than

the Scovill camera. Clearly, neither factory had a monopoly on the

smallest version of a camera. Rather, it is that the most compact

camera size is the version that is advertised in the catalogs: Scovill

for The Waterbury View, American Optical for

The

76 Camera

and its synonyms.

Comparison of a 5x8"

American Optical Co.

76 Camera

to a 5x8" Scovill Mg. Co.

76-type

Camera. Again, the design is essentially identical,

though the sizes and details (such as the sliding lens board) are not.

Unlike the Waterbury View example above, in this case, the American

Optical version is smaller than the corresponding Scovill version.

The high quality cameras were made from fancier and/or denser hardwoods, and finished using a technique called French polish. During the process, the pores in the wood are filled by successive applications of shellac (or other solvent-soluble lacquer) - rubbing the wood with a rag containing shellac. The final polish is achieved by a light application of another rag charged with solvent (ethanol) only. The result is a mirror-smooth but thin finish that reveals and displays the mahogany wood grain. Often, the metal parts of the high quality cameras were finished using a technique called draw-filing. A file is carefully applied in one direction, leaving uniform parallel lines and a very flat surface. As the camera was assembled, screw heads were made to all face the same direction - accomplished by installing many screws by trial and error until the uniform appearance is found. Finally, the screws being already installed, the draw-filing creates a nearly invisible screw to hardware interface.

The low quality cameras were made from cheaper woods, some not even hardwoods. The camera was assembled before being finished, using hardware that was probably cleaned, but otherwise just as it came from fabrication. The cameras were finished using varnish, clear or colored shellac, or black-pigmented shellac (called an ebonized finish in the trade). A camera varnish finish, often applied in one coat, displays a constant thickness whether on the surface or in the pores. On a porous wood such as mahogany or sycamore, it ultimately must be applied thicker than a French polish finish, and also displays a dip or indentation at every pore. All the wood was covered with finish, but the hardware often shows tarnished areas that did not receive a protective finish coat. The usual place to see this is on the rod & piston device that makes the platform rigid (visible in the camera on the right, above).

Wet-plate cameras from the American Optical factory are usually stamped American Optical Co., Manufacturer, New York. Dry-plate era cameras to 1889 have engraved silver-colored metal labels that read: American Optical Co., New York, Scovill Mfg. Co., Proptrs, as well as being stamped: American Optical Co., Scovill Mfg. Co. NY. By 1889, when Scovill Mfg. Co. was re-organized as The Scovill & Adams Co., the labels were molded celluloid plastic, and read American Optical Co., New York, The Scovill & Adams Co., Proprs.

The two factories sometimes produced cameras that are almost identical in design, except that the American Optical cameras have better woods and that higher grade of finish - i.e. there is often a Scovill camera model that is a cheaper version of an American Optical model.

Scovill confused the issue of whether a given camera is American Optical or Scovill by not being consistent in advertising and catalogs, Catalogs may refer to one or another camera being American Optical, or may imply that the entire catalog is the American Optical line. Many of the ads for the cameras use the same engraving to illustrate more than one model. For example, catalog 1 will advertise model 1 and model 2 cameras using one engraving. Another catalog will advertise model 2 only, using the previous model 1 engraving. The result is that it is not easy to determine whether a camera ought to be described as an American Optical camera or a Scovill camera, or to determine which factory in which it may have been made.

The Scovill & Adams Co.:

In 1889, Scovill Mfg. Co. was re-organized as The Scovill & Adams Co. At this time, all cameras, whether from the American Optical factory or the Peck factory, were marked: The Scovill & Adams Co., New York. Regardless of marking, the disparity of finish between the factories continued, and it is usually obvious when a camera is from the American Optical factory or from the Peck factory.

The camera lines were streamlined, and 1889 marks the extinction of many models and the introduction date of others. It is not a coincidence that, at this time, the Eastman Kodak Co. was rapidly expanding their roll film business and had introduced the extremely popular Kodak (push the button and we do the rest).

The Anthony & Scovill Co.:

Throughout the period 1870-1900, American Optical-Scovill and E. & H.T. Anthony & Co. were the two largest American manufacturers of photographic Cameras and supplies. They were competitors, often having similar camera models similarly priced. They both thrived in the era when a small number of committed amateur hobbyists or itinerant professionals carried their large wooden cameras and tripods into the field. But the Kodak introduced the entire population to carrying a small box that could capture their family images.

Anthony and Scovill merged in 1901. Due to the economic pressure of mainly Kodak, this was end of the line for the beautiful and lovingly made American Optical cameras - the Anthony and Scovill catalog of June, 1901 contains only view cameras from the Anthony line. Even when French polished, the Anthony & Scovill Co. camera finish does not approach the smoothness of the American Optical product.

The Anthony & Scovill Co. should have been viable during the introduction of roll film cameras, since they had purchased the Goodwin Roll Film Patent, a vaguely worded patent of flexible photographic film on a roll. The Eastman Kodak Co. had been producing roll film since 1889 the Kodak roll film cameras came to dominate the industry. In 1902, The Anthony & Scovill Co. sued Eastman Kodak Co. for patent infringement, and won the case in 1913, receiving five million dollars in the following year. But the damage had been done- Anthony & Scovill was now a minor player in a photographic industry where Kodak ruled.

ANSCO and Ansco Photoproducts:

In 1907, the name The Anthony & Scovill Co. was shortened to ANSCO. The era of the amateur hobbyist photographer was over. ANSCO may not even have manufactured view cameras at all - they are absent from ANSCO catalogs.

Agfa-Ansco:

In 1928, ANSCO merged with a German firm Agfa to become Agfa-Ansco. It was merged with other German companies in 1929 by a Swiss holding company, IE Chemie, later named GAF. During this time, view cameras were manufactured, but all marked Agfa-Ansco up to the Second World War. These are the last view cameras of interest. The company was sold to American investors as enemy assets in the 1960s.

Problems in American Optical / Scovill identification:

I have noted that cameras marked "American Optical" generally are made and finished better than cameras marked "Scovill". This is probably due to a company policy, but more than a little due to the fact that the Scovill Mfg. Co. (proprietors of the American Optical Co.) maintained two separate factories: the former John Stock factory (acquired 1867) in New York City from which cameras are generally marked "American Optical", and the former Samuel Peck factory (acquired 1857) in New Haven, CT, from which cameras are generally marked "Scovill".

From 1867, when the second factory was acquired, until about 1885, Scovill emphasized the difference between the highly regarded American Optical products and Scovill products. The emphasis was nowhere clearer than in their September 1884 catalog, in which the American Optical cameras are in a separate section of the catalog (pages 43-62) than the Scovill cameras (pages 73-78); the introductions to both sections are shown below. In addition, almost all of the Scovill cameras are prefaced by the term New Haven (the location of the Peck factory), e.g., The New Haven Compact View Cameras.

Scovill catalogs and advertising often, if not always, featured a mixture of cameras made in the American Optical factory and cameras made in the Scovill factory. They were equally as often lax about saying whether a given camera was an American Optical or a Scovill product. This has naturally led to some confusion regarding the maker of a model. Despite the fact that I have a separate thumbnail web page for each of the companies (so as to limit the number of models on each page), it can be difficult to assuredly assign a camera to one or the other maker/factory.

In addition, several instances are known of models which appear to have been made by both factories, but only advertised to have been made by one. A common example is the Scovill Waterbury and American Optical Waterbury-Type. The Waterbury is a common amateur rear-focusing, single swing, front rise, non-tapered bellows camera made of varnished sycamore wood and un-lacquered brass (except on its edges where the varnish from the wood has slopped over onto the brass - apparently, the varnish is applied after assembly). The Waterbury-Type is virtually the same design, but made from dark, tight-grained, French Polish lacquered mahogany and fancy, draw-filed brass hardware on which all the screw slots have been laboriously aligned. The Waterbury is in every catalog, whereas the Waterbury-Type seems to only appear in remainder sale lists. Other examples are the Scovill Acme and the American Optical Acme, and the Scovill St. Louis and the American Optical St. Louis (discussed on the Scovill page).

Formerly, I had separate American Optical and Scovill thumbnail pages in this web site. For these reasons discussed above, the pages have been merged as one American Optical/Scovill page.

American

Optical / Scovill Patents:

243,136; Jun 21, 1881; wooden plateholder

(original patentee: J. Milton Howe). This patent was also used by

Blair.

277,787; May 15, 1883; blackboard slide for

plateholder (patent held by Blair, but Scovill used it by royalties

paid)

283,589; Aug 21, 1883: Flammang revolving back (always stamped

Flammang's)

328,664; Oct 20, 1885: rod & cylinder system for making bed rigid (by

Flammang, and often stamped Flammang's Patent)

331,448; Dec. 1, 1885: front & rear focusing, two

bellows camera (The Ripley Camera); George Ripley, assignor to Scovill

Mfg. Co.

376,983; Jan 24, 1888: plate holder (original patentee: Willard H.

Fuller, assigned to Scovill Mfg. Co.).

402,154; Apr 30, 1889: print frame (original

patentee: Willard H. Fuller, assigned to Scovill Mfg. Co.).

428,809; May 27, 1890:

wooden plate holder (original patentee: Willard H. Fuller, assigned to

The Scovill & Adams Co.).

436,891; Sep 16, 1890: view

camera having struts, essentially

The Irving

Camera (Washington Irving Adams, for The Scovill & Adams

Co.).

Scans of number

of catalogs can be found

here.

Scans of American Optical and Scovill catalogs are

here.

Green Links

indicate dry plate cameras.

Light Blue Links indicate wet plate

cameras.